Author: Robertson, David

Conceptual Article | Open Source

Revised: N/A

Published Online: 2024 November – All Rights Reserved

APA Citation: Robertson, D. M. (2024, November 3). The Contrastive Inquiry Method: An Equation for Better Understanding. DMRPublications. https://www.dmrpublications.com/contrastive-inquiry-method/

An Equation for Better Understanding

-

Abstract

-

Full Text

-

PDF / Download

-

Legal & Contact

-

Author’s Note

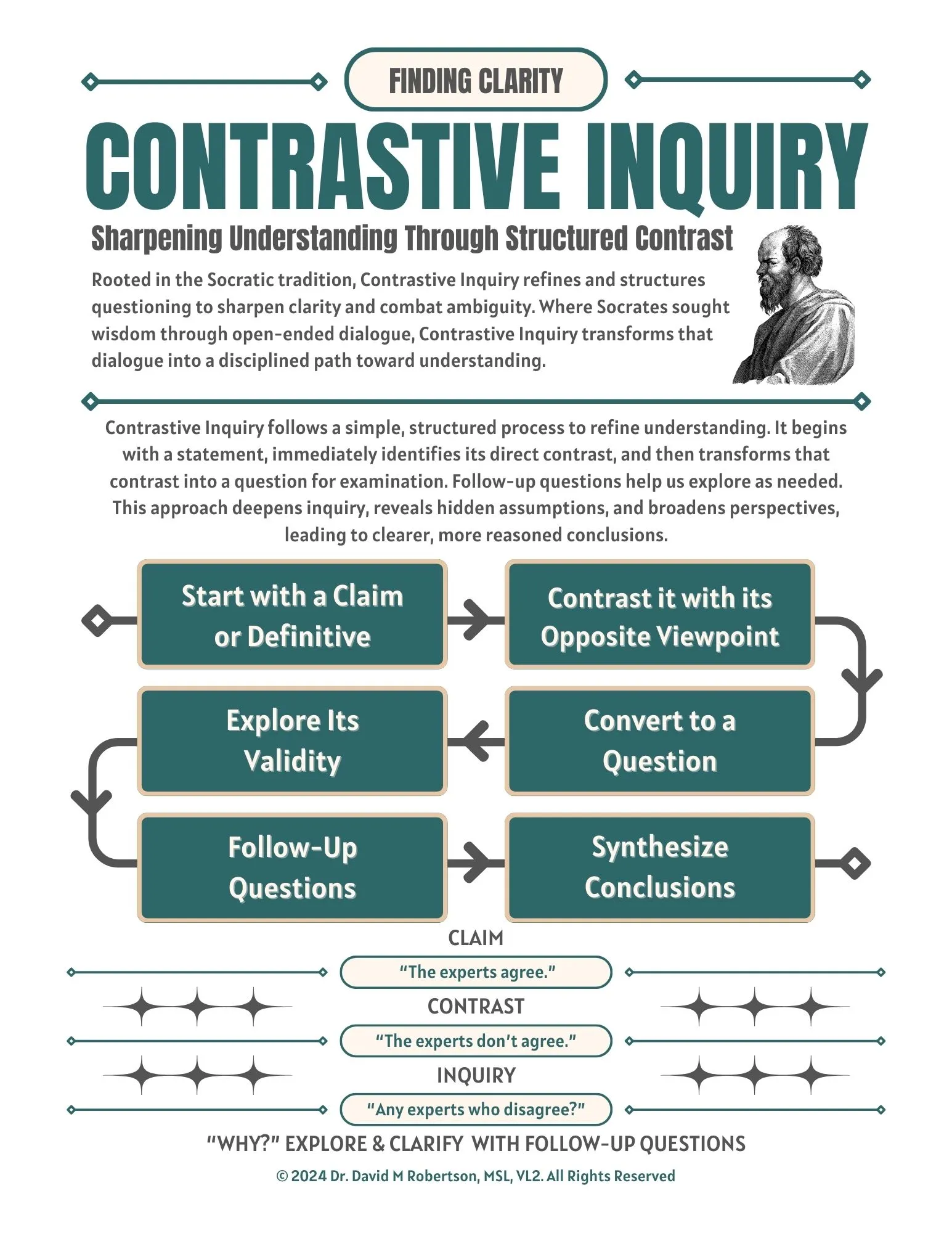

This article introduces the Contrastive Inquiry Method, a structured approach to questioning that enhances understanding by examining contrasting perspectives. Rooted in the principles of Socratic questioning, this method narrows the focus and clarifies complex topics by systematically turning opposing statements into insightful questions. By exploring these contrasts, the method encourages deeper inquiry, uncovers hidden nuances, and fosters a balanced view of contentious issues. This article outlines the importance of situational analysis, highlights key examples, and discusses how the method is a powerful tool to combat Epistemic Rigidity and improve decision-making and outcomes in various contexts.

Introduction

The key to deeper understanding often lies in contrast. Through contrast, we uncover the nuanced relationships between opposing viewpoints, clarifying complex topics in ways that simple inquiry cannot. Enter the Contrastive Inquiry Method, a structured approach that refines traditional Socratic questioning by focusing on direct contrast to clarify inquiry scope and enhance understanding. By systematically transforming contrasting statements into questions, we can uncover hidden nuances, challenge assumptions, and achieve a more balanced understanding of any subject.

Advancing Beyond Socratic Questioning

While rooted in the Socratic Method, the Contrastive Inquiry Method goes beyond it by providing a structured pathway to avoid ambiguity. The Socratic Method encourages broad, open-ended questioning to confront assumptions, yet this openness can sometimes dilute focus and lead to tangential thinking. Contrastive Inquiry, in contrast, is inherently structured, prompting specific, actionable questions that maintain clarity and direction, improve understanding, and enhance understanding.

For instance, where Socratic questioning might ask, “What is the nature of truth?” the Contrastive Inquiry Method would start with a concrete statement, such as, “That is true,” followed immediately by its direct contrast: “That is false.” From there, the inquiry sharpens by turning that contrasting statement into a question of exploration: “Is there any evidence to suggest that is false?” Of course, there is no wrong way to formulate your contrasting question so long as it does not reaffirm or explore the original concrete statement, avoiding Confirmation Bias. From there, we develop follow-up questions that naturally arise from the information we examine.

This approach reduces initial uncertainty by anchoring each question—and subsequent questions—in direct contrast to the original claim or belief, fostering clarity, balance, and actionable insights that propel inquiry and problem-solving forward. When no contrasting information emerges, the original statement is likely well-founded. Of course, not all contrasting information is accurate or valid. Hence, if contrasting information is discovered, we objectively evaluate its validity, recognizing that valid contrasts inherently suggest further gaps that merit exploration or the explorer’s unexposed ignorance of the matter.

Further, Contrastive Inquiry differs from Socratic Questioning in that it focuses on real-world application rather than philosophical abstraction. Rather than merely exposing contradictions, it systematically challenges the often rigid mental framework surrounding an issue. This is to say that Contrastive Inquiry offers a more targeted and practical approach to uncovering gaps in knowledge and broadening perspectives for those seeking actionable insights- whether in decision-making, policy formulation, or strategic planning.

Process of Contrastive Inquiry

To employ Contrastive Inquiry, begin with a statement or belief and immediately identify its direct contrast. Then, transform this contrast into a question that invites examination. This structured process is highly adaptable and can be used for issues of any complexity. Consider the following example.

Example 1: “The experts agree.”

- Statement: “The experts agree.”

- Contrast: “The experts don’t agree.”

- Inquiry: “Are there experts who disagree?”

- Follow-Up Questions Rooted in Contrast

The inquiry drives us to investigate contrasting expert opinions often present in any field or topic. Exploring these differences prompts further questions, such as, “Why don’t these experts agree?” leading us to uncover technical details, methodologies, or even political biases contributing to the divergence. In broadening our understanding, we become more informed and less swayed by rhetoric and misinformation, developing a balanced view rooted in the full spectrum of perspectives. The benefit comes from having a fuller picture of the issues, which allows us to make more informed decisions and avoid several dangerous components of Epistemic Rigidity, typically leading to better outcomes.

Contrastive Inquiry and Epistemic Rigidity

Contrastive Inquiry is especially valuable in addressing Epistemic Rigidity, the resistance to new information or perspectives that conflict with established beliefs. This cognitive inflexibility stifles innovation and critical thinking, keeping individuals and groups entrenched in outdated beliefs even when faced with evidence to the contrary. However, it does so by exploiting our natural curiosity.

Deliberately seeking contrast can disrupt rigid mental frameworks, encouraging open-minded engagement with opposing viewpoints. For example, in asking, “Are there experts who disagree?” we unconsciously break from the mental inertia that sustains unexamined beliefs, transforming inquiry into an enjoyable discovery-oriented process rather than one of mere confirmation or defense. Similarly, this method cleverly addresses confirmation bias by emphasizing contrasting perspectives, helping individuals move past entrenched views, and fostering intellectual growth.

Cultivating Perpetual Learning

To be an expert, one must adopt a perpetual learning mindset rooted in a desire for accuracy (Heslin & Keating, 2017; Persky & Robinson, 2017). Accordingly, Contrastive Inquiry positions accuracy as the ultimate goal while ensuring we lead with questions rather than assumptions or premature conclusions. Moreover, rather than settling on any single perspective, it continuously engages with diverse viewpoints, yielding a well-rounded understanding of complex issues and understanding that few things are so simple. This perpetual learning approach leads us to explore the full spectrum of ideas and evidence, facilitating better, more informed decisions and typically providing better outcomes. Real-world examples illustrate this truth.

Example 2: “Red meat is bad for you.”

- Statement: “Red meat is bad for you.”

- Contrast: “Red meat is good for you.”

- Inquiry: “Is there evidence that red meat can be good for you?”

- Follow-Up Questions Rooted in Contrast

Exploring this question objectively reveals a slew of potential health benefits. Hence, a natural balance has been struck by appreciating that red meat is nutritionally rich in elements like zinc and heme iron, though it may also carry health risks depending on factors such as processing or nutritional status of the animal (Barnett et al., 2019; Davis et al., 2022). Examining both sides reveals nuanced situational benefits and risks, leading us to more balanced health decisions tailored to individual needs. This process transcends simple arguments for or against red meat and promotes a more sophisticated, situationally informed approach.

Example 3: “Screen time is harmful to children.”

Contrastive Inquiry can also reveal unexpected insights into a topic often influenced by societal narratives.

- Statement: “Screen time is harmful to children.”

- Contrast: “Screen time is beneficial to children.”

- Inquiry: “Is there evidence that screen time can benefit children?”

- Follow-Up Questions Rooted in Contrast

Note how the concrete claim brings emotion into the examination. This emotion sounds about right, but it can also keep us from a more profound understanding. Indeed, research indicates excessive screen time is linked to attention deficits and sleep disruption (Priftis & Panagiotakos, 2023). However, research also demonstrates that certain screen-based activities can promote learning and creativity (Tang et al., 2022). Strategic follow-up questions, such as “What types of screen time are beneficial?” and “How does screen time affect children of different ages?” deepen our understanding and provide us with situational utility. Hence, rather than adopting an all-or-nothing stance, this nuanced approach promotes a tailored view that considers individual needs and specific contexts, allowing us to capitalize on the benefits while limiting or mitigating any detriment.

The Value of Situational Approaches

Contrastive Inquiry’s emphasis on situational context fosters precise, adaptable decision-making. Challenging binary thinking enables solutions that reflect complexity rather than reducing issues to “right” or “wrong.” This situational flexibility is especially valuable for adapting to changing circumstances, promoting open-mindedness, and encouraging continuous learning (Klein, 2011).

Potential Benefits of Situational Thinking with Contrastive Inquiry:

- Avoiding Oversimplification: Situational inquiry prevents the pitfalls of “one-size-fits-all” solutions, promoting nuanced thinking that respects the complexity of individual issues.

- Supporting Flexible Problem-Solving: In fast-evolving fields, rigid solutions often fall short. Situational thinking allows for dynamic adaptation and utilization of new insights.

- Improving Outcomes: By tailoring responses to unique situations, situational inquiry promotes more effective problem-solving, especially in domains like leadership, health, and education.

- Encouraging Intellectual Curiosity: A situational approach inherently values exploration and ongoing discovery, fostering intellectual openness rather than dogmatic thinking. Similarly, it allows us to step away from the dangers of the Dunning-Kruger Effect by fostering perpetual learning.

In essence, Contrastive Inquiry refines critical thinking by helping us engage deeply with complex issues for more balanced and informed conclusions. Systematically contrasting perspectives help dismantle rigid thinking and encourage a flexible approach. Ultimately, this openness enables us to interact with diverse viewpoints, moving closer to true accuracy and nuanced understanding.

Importance Statement

The Contrastive Inquiry Method is important because it supports a more balanced examination of complex issues, often revealing overlooked nuances and offering a framework for more precise, comprehensive perspectives. However, it should be noted that such insight may cause discomfort when any accuracy discovered demands a rejection of the old information. This discomfort, a phenomenon known as ‘Cognitive Dissonance,’ is usually extreme during emotionally charged discussions (Fontanari et al., 2011).

It should be warned that oversimplified viewpoints and emotional responses can be dangerous. Emotional investments can unintentionally obscure objective analysis, while limited perspectives can make us vulnerable to narratives shaped by those with vested interests (Konieczny, 2023). Moreover, it allows others to weaponize and exploit our ignorance against us (McGoey, 2012). This understanding provides relevance to the idea that “the ignorant are easily led.” Hence, we must relentlessly pursue knowledge and insight to avoid contortion and manipulation.

We should also view an emotional spike as a warning sign of a gap in perspective rooted in oversimplification. This is especially true regarding public discourse. Public discourse often becomes oversimplified in highly charged discussions, fixating on opposing viewpoints that typically leave more profound questions unasked (Doornbosch, van Vuuren, & de Jong, 2024; Wilson, 2015). The student loan debate demonstrates this perfectly, frequently devolving into an emotional “all-or-nothing” framing that has long forgotten the issue’s broader contexts (Goldrick-Rab & Steinbaum, 2020).

When complex issues are reduced to emotionally charged, binary choices, the result is often a failure to consider alternative perspectives, leading to fallacious reasoning known as the “either-or fallacy” or “false dilemma” (Tomić, 2013). A fallacy, a mistaken belief or argument rooted in invalid reasoning, undermines rational discourse by constraining thought to overly simplistic conclusions (Conces & Walters, 2023). This reductionist approach promotes rigidity in thought, especially in discussions driven by strong emotional or ideological attachments (Lissack, 2016). Consequently, these rigid frameworks distort the issue’s complexity, making fallacious reasoning more likely (Weston, 1984).

One can note the cyclical nature of the problem. To avoid such pitfalls, meaningful inquiry demands an openness to exploring nuanced alternatives, which can be challenging for those deeply invested in a specific narrative (Brisson et al., 2018). Recognizing this truth, the Contrastive Inquiry Method provides a way out of the cycle, a structured approach to counteract these mechanisms. When utilized effectively, this method helps to expand the conversation and open potential pathways for solution-based thinking built upon a foundation of accuracy. Only then can we have meaningful discourse.

To appreciate the power of the Contrastive Inquiry method, we must understand that emotion is a primary driver of bias, negatively influencing our interpretations and judgments (Kirman, Livet, & Teschl, 2010). Specifically, emotions such as fear, anger, joy, and frustration can lead us to form entrenched perspectives, which often restrict objective analysis and seemingly force us to defend our misconceptions (Sharma, Wade, & Jobson, 2023; Weeks, 2023; Kassam, 2015; Lerner, Dorison, & Klusowski, 2023). In the case of student loans, many people hold firmly rooted but emotional views, which create mental barriers to balanced discussion. This makes the topic an excellent case study to explore.

A Case Study of Discovery Using the Contrastive Inquiry Method

Disclaimer: The following case study is intended only to illustrate how the Contrastive Inquiry Method reveals underlying factors and often overlooked perspectives. The example used here is commonly a sensitive topic; however, the intent is not to provoke or solve but to demonstrate how this approach facilitates deeper understanding by encouraging questions that might otherwise go unasked. Furthermore, it should be noted that this method is not meant to eliminate debate but to simply expand inquiry and understanding. This case study will present many questions. Readers may follow different paths of exploration using this method, each yielding different but valuable insights.

Examining the Core Narrative

A prevailing narrative in the student loan discussion is that students should bear full responsibility for their educational debts, as these debts result from personal choices. However, this perspective frames student debt as an isolated matter solely focused on the student with no broader societal influences, implications, or responsibilities. Few things are so simple. Given that this belief is widely accepted, we must first ask, is this perspective truly accurate?

Many are going to default to “yes” without any further consideration. However, this merely demonstrates how easily bias can drive our decision processes and destroy our willingness to examine potential alternatives or solutions. Of course, the structure of the question itself may be flawed. Indeed, the Contrastive Inquiry Method encourages us to set aside preconceived notions to explore this question effectively. Furthermore, it restructures the question to become less threatening, which should temper our emotional investment. If we can temper our emotions momentarily, we can go forth with genuine curiosity, leading to insights we might otherwise miss. The benefit is simple: if knowledge is power, then this method provides us with the path to the power we seek.

Challenging Assumptions

Indeed, numerous questions could be explored. Several questions generated for this paper include: Are our current narratives about student loans grounded in facts or shaped by societal pressures and external influences? Who benefits most from the existing structure, and could vested interests influence dominant opinions about student loans?

While these questions are helpful, we must, once again, note the visceral urge to answer them from a defense position. As previously alluded, we often find ourselves being pulled by unconscious biases (Banaji & Greenwald, 2016; Ross, 2020). However, we must also understand that if our bias is driving, any questions we ask will likely be biased, particularly if we have prior knowledge of the topic (Prior, Sood, & Khanna, 2015). As a result, any answers we find during exploration are also likely biased (Burghardt, Hogg, & Lerman, 2018). To fix this problem, we must strategically reframe the question, and we do so by contrasting a definitive statement.

Shifting Perspectives

Take the definitive statement and flip it using contrast. For instance:

- Statement: “Student loans are a student’s problem.”

- Contrast: “Student loans are not just a student’s problem.”

- Question: “Is there evidence suggesting that student loans are a problem for more than just the student?”

Similarly:

- Statement: “Education benefits only the student.”

- Contrast: “Education benefits more than the student.”

- Question: “Does education benefit anyone beyond the student?”

Genuine exploration of these questions demonstrates that while higher education benefits the individual student, it also ultimately contributes to societal interests in a variety of ways (Rhoades, 1983). Of course, true understanding often arises from cause-and-effect analysis, which is ideal for follow-up question formulation (Andersen & Fagerhaug, 2006). For example, in this case, we learn that higher education typically correlates with increased income (Hout, 2012). With this new awareness, inquiry might expand further, encouraging questions about an educated populace’s disproportionate contributions to society, from higher taxes to more abstract contributions to public welfare such as job creation or knowledge distribution (Agénor & Moreno-Dodson, 2006; Albouy, 2009). Already, this analysis has provided a more nuanced view and additional questions, integrating broader social benefits and responsibilities.

Any discovered insight deserves follow-up questions. For example, exploring the previous contrasting insights might also reveal profound questions about fairness, as this interconnected flow demonstrates some of the broader societal advantages of an educated populace and how those who make less money still benefit from various services and public goods despite their reduced level of comparative investment. Hence, if equality is truly valued, if student loans are seen solely as the student’s responsibility, and if the benefit is theirs alone, should educated individuals receive a tax rate reduction to match the tax rate of lower earners? Of course, even these questions could be contrasted. For example, in the spirit of capitalism, should society at large be privy to the benefit from the contributions of educated individuals without sharing in the cost of that education? What do we call someone who demands or partakes in benefits without expecting to provide some level of investment?

Historical Context and Common Ground

The Contrastive Inquiry Method can also bring forward historical perspectives that add further dimensions not otherwise considered. In exploring the role of education in society, for example, we might discover that figures like Thomas Jefferson advocated for accessible education as a foundation of national stability. This makes sense because supporting, loving, defending, or exercising something you do not know or understand would be difficult. Specifically, Jefferson wrote:

“Preach, my dear Sir, a crusade against ignorance; establish and improve the law for educating the common people. Let our countrymen know that the people alone can protect us against these evils, and that the tax which will be paid for this purpose is not more than the thousandth part of what will be paid to kings, priests, and nobles who will rise up among us if we leave the people in ignorance.”

— Thomas Jefferson to George Wythe, August 13, 1786

Therein lies another key benefit of this method: its capacity to reveal underlying conflicts in values and assumptions, which can deepen our understanding and appreciation of complex issues. For instance, the preceding quote provides vital context and perspective, which also likely presents a paradox for most: individuals with constitutional beliefs aligned with Jefferson’s vision may feel conflicted if they oppose shared education funding, while advocates of loan forgiveness might face tension when grappling with their critique of historical figures like Jefferson. However, this can be highly valuable. Examined objectively, this insight could serve as a basis for finding common ground between these groups, potentially broadening perspectives and opening a path for constructive dialogue on solutions.

Power of Contrastive Inquiry

This case study demonstrates how the Contrastive Inquiry Method exposes biases, broadens understanding, and counters potential limiting influences. Addressing such influences is essential, as our biases can leave us vulnerable to supporting initiatives or ideas that may not truly serve our interests or align with our principles (Brafman & Brafman, 2008). Rather than prescribing solutions for the problem discussed, this case study merely exemplifies how structured inquiry can reveal hidden knowledge gaps and perspectives and foster informed decision-making by challenging assumptions, making it an essential tool for addressing multifaceted social issues. However, an additional benefit is that it can allow us to address our ignorance of a topic by exposing and filling unknown knowledge gaps.

Discovering Gaps: Exploring Context for Better Problem Solving

While Contrastive Inquiry often yields more robust answers, it also exposes inherent reasoning gaps—those unexamined assumptions and blind spots that obstruct genuine understanding. It is important to note that asserting definitive statements, even internally, creates mental blocks that discourage deeper exploration (Adams, 2019). Only contrasting information can balance it out. Unfortunately, these mental blocks set mental boundaries that narrow our focus and limit our ability or desire to discover broader contexts, often resulting in diminished agency and uninformed, limiting decisions (Rivero-Obra, 2024).

Using the student loan debate as an example demonstrates how easily we can overlook an issue’s broader societal dimensions. The key is truly in the contrast because while we are often encouraged to focus our attention on the costs of educational investment, the reality is that research suggests that the societal and economic costs associated with an uneducated population—including higher spending on healthcare, social services, and criminal justice—can far exceed the costs of providing quality education in the first place, which would ultimately reduce the costs associated with having an uneducated society by ensuring that more people were educated (Douglass, 2018; Bell, Costa, & Machin, 2022; Muennig, 2006; Telfair & Shelton, 2012). One might wonder about the motives for such distortions in public discourse. In an attempt to find these answers, one might also find an interesting intersection between education, income, financial institutions, and government policies.

Logically, ignorance about the specifics of student loans, including their unique structure, can lead to oversimplified viewpoints and emotional responses, especially if unexamined assumptions lead some to dismiss the issue based on their own experiences or beliefs. However, as Carlson (2020) points out, only a proper understanding of the full nature of these loans will allow for an informed debate, which might also expose the state’s potentially criminal role. Therein lies a valuable lesson of how unintentional or willful ignorance can significantly reduce opportunities for accountability or how those seeking to avoid accountability can exploit ignorance to protect themselves. Does this truth expose the motive?

While the previous point is compelling, the question of precedence might also be explored. Historical documents like The Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 demonstrate how early American policy emphasized community-based education funded through federal support but independent of federal control (Victor, 1900). Scholars such as Carl Kaestle note that the original federal role was largely financial, intended to encourage state and local educational efforts rather than to establish centralized oversight (Kaestle, 1983). Lawrence A. Cremin’s work, American Education: The Colonial Experience, further supports the view that education was intended as a community-supported endeavor separate from distant governmental authority (Cremin, 1974).

The evidence is mounting, and it seems to suggest that the government was supposed to fund education but not control it. If so, then what changed, and why? After all, many still argue that the decentralized approach offers a more balanced educational model than today’s system, where federal involvement has grown in ways that shift the focus of education away from community needs (Bray, 1996). Is that true?

This broader perspective likely raises new questions: What are the pros and cons of returning to a system of locally managed, federally funded education? What are the benefits or potential issues with the current federally controlled education system? What caused this shift from decentralized to centralized education in the first place, and why? Note how these questions compound, resulting in endless opportunities for further exploration and understanding. That is both the point and the benefit. Of course, this compounding of question and exploration starkly contrasts with defending definitive or preconceived statements, leading to predetermined and often manipulated conclusions.

Indeed, numerous other questions could be asked, but analyzing current issues without addressing these contextual changes can lead to an incomplete understanding of the root problems. As Winter and Jackson (2004) astutely suggest, gaps in understanding limit meaningful discourse and prevent more comprehensive solutions. The student loan topic is no exception.

Of course, we may have discovered a terrible, self-feeding loop of ignorance. Indeed, state control over education continues to increase, as do educational gaps. As previously stated, education gaps result in higher societal costs. These higher costs typically require higher revenues. Higher revenues typically result in larger government systems and more state controls. Can we then expect more educational gaps as state control over education increases? What is the fallout of such a spiral?

This insight should prompt questions about who or what truly benefits from this structure. It should also prompt questions regarding its impact on society and the convenient lack of knowledge regarding its correction, being that those tasked with education have seemingly omitted such knowledge from the curriculum. Moreover, it should probably alter current perceptions regarding how that system preys upon those who do not and could not fully understand the ramifications of such loans, and why it seems that very little is being done to address the problem.

Interestingly, Jefferson also warned of such potential misalignments between power and public welfare, noting in his 1816 letter to George Logan that “banking establishments are more dangerous than standing armies.” His concern seems particularly relevant today, as large financial institutions profiting from the student loan crisis are also known to manipulate policymakers through donations and lobbying, often at the expense or detriment of their constituents. This insight might explain our politicians’ lack of motivation to fix the problem. The question might then become: What is the true cost of allowing these interests to shape policy?

And this example could go on. Again, this example is not meant to solve the problem. However, regardless of our final position on the matter and what information we might examine along the way, the Contrastive Inquiry Method has proven effective. Ultimately, this method broadens our analysis beyond the initial problem and allows us to expand our knowledge on related matters. This expanded knowledge allows us to make more informed inquiries and decisions, typically resulting in better outcomes.

In this example, most would likely agree that these new perspectives seemingly demonstrate that education funding issues are likely symptomatic of a much larger issue: an imbalance of power that prioritizes institutional profit and control over the well-being of individuals and communities (Nyberg, 2021; Shaw, 2008; Statva, 2012). If one were so inclined, that would likely be a great place to begin a resolution journey. Nonetheless, the takeaway of this section should be that we can only create space for understanding and more innovative, effective solutions when we are willing to question and understand these foundational gaps often present in binary, fallacious perceptions.

Final Thoughts

As you can see, Contrastive Inquiry effectively uncovers important variables and underlying truths. While it requires effort and may yield uncomfortable or complex answers, it ultimately brings us closer to accuracy, which is preferable to becoming a living illustration of the negative side of the Dunning-Kruger Effect. In our example, you can note the numerous variables identified that would likely remain unexamined by those focused solely on defending their positions related to student decisions.

Only with true understanding can we begin to address the problem accurately. Again, try not to be distracted by the politics of the example chosen for this examination. We could have explored many other topics and reached a very similar conclusion. Sure, this case study exposes some manipulative tactics of powerful entities that influence families and communities, pushing them to unwittingly support a system that rejects foundational principles and burdens communities and future generations. However, we should note that where we ended differed greatly from where we began. This is very good because while it is true that we cannot solve a problem that has not been properly identified, we also cannot properly identify the true scope of a problem without Contrastive Inquiry.

The point is that, regardless of the topic, without examining these contrasting views, we risk missing the covert elements critical to a more complete understanding. One can note the back-and-forth swing this examination took. That is the inherent balancing effect that comes from this approach, and there is still much that could be discussed or examined. However, when we miss these important details due to biased assumptions and emotional contortions, we are more likely to make biased decisions that hinder our ideal outcomes. Ultimately, Contrastive Inquiry is the key that opens the door to our escape from Epistemic Rigidity (Robertson, 2024) and, by extension, the Adversity Nexus (Robertson, 2023).

“Fix reason firmly in her seat and call to her tribunal every fact, every opinion. Question with boldness even the existence of a god because, if there be one, he must more approve the homage of reason than that of blindfolded fear … I repeat that you must lay aside all prejudice on both sides and neither believe nor reject anything because any other person, or description of persons have rejected or believed it. Your own reason is the only oracle given to you by heaven, and you are answerable not for the rightness but uprightness of the decision.” – Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, Paris Aug. 10. 1787.

Limitations:

While the Contrastive Inquiry Method offers a structured approach to understanding contrasting perspectives, its effectiveness depends heavily on information quality and availability. In some cases, limited access to credible or comprehensive data can hinder meaningful inquiry. Additionally, the method requires cognitive flexibility and openness to discomfort, which may be challenging for individuals suffering from Epistemic Rigidity and deeply entrenched in their views. Furthermore, certain issues may present overly complex or ambiguous contrasts that are difficult to resolve through this method alone, requiring additional tools for thorough analysis.

Discussion:

The Contrastive Inquiry Method provides a valuable framework for navigating complex topics by encouraging a deeper exploration of opposing viewpoints. Focusing on contrasts and transforming them into questions promotes a more dynamic and nuanced understanding of various subjects, challenging rigid thinking patterns. This method is a practical tool to combat Epistemic Rigidity, foster critical thinking, and enhance decision-making. However, its success is contingent upon the willingness to engage with diverse perspectives and the availability of credible evidence. Expanding its application to different domains will likely reveal further potential for refining both individual and collective understanding.

Conclusion

The ultimate takeaway is that achieving a better understanding is rooted in contrast. By examining opposing views and questioning our assumptions’ validity, we open avenues for more profound insight. This Contrastive Inquiry Method leads to a more comprehensive view of the topic and fosters a mindset of continuous inquiry. The equation is simple: statement + contrast + question = understanding. With each question we ask, we push ourselves further toward clarity and accuracy, which are the true goals of honest inquiry, not simply being “right.”

Acknowledgments:

I extend my heartfelt gratitude to my students for their encouragement and willingness to allow me to experiment with these insights throughout the development of the Contrastive Inquiry Method. Their support has been instrumental in shaping my ideas and refining the theoretical framework presented in this paper.

Conflict of Interest:

Dr. David Robertson declares no financial or personal relationships that could potentially bias this work within the scope of this research. This includes but is not limited to employment, consultancies, honoraria, grants, patents, royalties, stock ownership, or any other relevant connections or affiliations. He affirms that the research presented in this paper is conducted in an objective manner, and there are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Resources:

Adams, J. L. (2019). Conceptual blockbusting: A guide to better ideas. Basic Books.

Agénor, P. R., & Moreno-Dodson, B. (2006). Public infrastructure and growth: New channels and policy implications (Vol. 4064). World Bank Publications.

Albouy, D. (2009). The unequal geographic burden of federal taxation. Journal of Political Economy, 117(4), 635-667.

Andersen, B., & Fagerhaug, T. (2006). Root cause analysis. Quality Press.

Banaji, M. R., & Greenwald, A. G. (2016). Blindspot: Hidden biases of good people. Bantam.

Barnett, M.P., Chiang, V.S., Milan, A.M., Pundir, S., Walmsley, T.A., Grant, S., Markworth, J.F., Quek, S.Y., George, P.M., & Cameron-Smith, D. (2019). Plasma elemental responses to red meat ingestion in healthy young males and the effect of cooking method. European Journal of Nutrition, 58, 1047-1054.

Bell, B., Costa, R., & Machin, S. (2022). Why does education reduce crime?. Journal of political economy, 130(3), 732-765.

Brafman, O., & Brafman, R. (2008). Sway: The irresistible pull of irrational behavior. Crown Currency.

Bray, M. (1996). Decentralization of education: Community financing (Vol. 36). World Bank Publications.

Brisson, J., Markovits, H., Robert, S., & Schaeken, W. (2018). Reasoning from an incompatibility: False dilemma fallacies and content effects. Memory & Cognition, 46, 657-670.

Burghardt, K., Hogg, T., & Lerman, K. (2018, June). Quantifying the impact of cognitive biases in question-answering systems. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (Vol. 12, No. 1).

Doornbosch, L. M., van Vuuren, M., & de Jong, M. D. (2024). Moving beyond us-versus-them polarization towards constructive conversations. Democratization, 1-27.

Carlson, S. M. (2020). The US student loan debt crisis: State crime or state-produced harm?. Journal of White Collar and Corporate Crime, 1(2), 140-152.

Conces, R. J., & Walters, M. (2023). Something Called the ‘False Dilemma Fallacy’(FDF): A Return to Formalization Just This Time. Informal Logic, 43(2), 280-289.

Cremin, L. A. (1974). American education, the colonial experience 1607-1783. British Journal of Educational Studies, 22(1).

Davis, H., Magistrali, A., Butler, G., & Stergiadis, S. (2022). Nutritional Benefits from Fatty Acids in Organic and Grass-Fed Beef. Foods, 11.

Douglass, G. K. (2018). Economic returns on investments in higher education. In Investment in Learning (pp. 359-387). Routledge.

Fontanari, J. F., Perlovsky, L. I., Bonniot-Cabanac, M. C., & Cabanac, M. (2011, July). Emotions of cognitive dissonance. In The 2011 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (pp. 95-102). IEEE.

Goldrick-Rab, S., & Steinbaum, M. (2020). What is the problem with student debt. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 39(2), 534-540.

Heslin, P. A., & Keating, L. A. (2017). In learning mode? The role of mindsets in derailing and enabling experiential leadership development. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(3), 367-384.

Hout, M. (2012). Social and economic returns to college education in the United States. Annual review of sociology, 38(1), 379-400.

Kaestle, C. F. (1983). Pillars of the republic: Common schools and American society, 1780-1860 (Vol. 154). Macmillan.

Kassam, K. S. (2015). Emotion and decision making. Annu. Rev. Psychol, 66, 33-1.

Kirman, A., Livet, P., & Teschl, M. (2010). Rationality and emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 365(1538), 215-219.

Klein, G. A. (2011). Streetlights and shadows: Searching for the keys to adaptive decision making. Mit Press.

Konieczny, M. (2023). Ignorance, disinformation, manipulation and hate speech as effective tools of political power. Policija i sigurnost, 32(2/2023.), 123-134.

Lerner, J. S., Dorison, C. A., & Klusowski, J. (2023). How do emotions affect decision making?. Emotion theory: The Routledge comprehensive guide, 447-468.

Lissack, M. (2016). Don’t be addicted: The oft-overlooked dangers of simplification. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 2(1), 29-45.

McGoey, L. (2012). The logic of strategic ignorance. The British journal of sociology, 63(3), 533-576.

Muennig, P. A. (2006). Healthier and wealthier: Decreasing health care costs by increasing educational attainment.

Nyberg, D. (2021). Corporations, politics, and democracy: Corporate political activities as political corruption. Organization Theory, 2(1), 2631787720982618.

Persky, A. M., & Robinson, J. D. (2017). Moving from novice to expertise and its implications for instruction. American journal of pharmaceutical education, 81(9), 6065.

Priftis, N., & Panagiotakos, D. (2023). Screen Time and Its Health Consequences in Children and Adolescents. Children, 10.

Prior, M., Sood, G., & Khanna, K. (2015). You cannot be serious: The impact of accuracy incentives on partisan bias in reports of economic perceptions. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 10(4), 489-518.

Rhoades, G. (1983). Conflicting interests in higher education. American Journal of Education, 91(3), 283-327.

Rivero-Obra, M. (2024). Misunderstandings and Difficulties in Making Sense of the Action. Problemos, 106, 147-158.

Robertson, D. (2023, Aug 28). The Adversity Nexus Theory. The Journal of Leaderology and Applied Leadership. https://jala.nlainfo.org/the-adversity-nexus-theory/

Robertson, D. M. (2024, June 26). Epistemic Rigidity: A Theoretical Framework for Understanding Cognitive Barriers to Knowledge Advancement. DMRPublications. https://www.dmrpublications.com/epistemic-rigidity/

Ross, H. J. (2020). Everyday bias: Identifying and navigating unconscious judgments in our daily lives. Rowman & Littlefield.

Shaw, H. J. (2008). The Rise of Corporatocracy in a Disenchanted Age. Human Geography, 1(1), 1-11.

Sharma, P. R., Wade, K. A., & Jobson, L. (2023). A systematic review of the relationship between emotion and susceptibility to misinformation. Memory, 31(1), 1-21.

Statva, M. (2012). Corporatocracy: New Abutment of the Economy and Politics of the United States of America (Master’s thesis, Eastern Mediterranean University (EMU)-Doğu Akdeniz Üniversitesi (DAÜ)).

Tang, C., Mao, S., Naumann, S. E., & Xing, Z. (2022). Improving student creativity through digital technology products: A literature review. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 44, 101032.

Telfair, J., & Shelton, T. L. (2012). Educational attainment as a social determinant of health. North Carolina medical journal, 73(5), 358-365.

Tomić, T. (2013). False dilemma: A systematic exposition. Argumentation, 27(4), 347-368.

Victor, F. F. (1900). Our Public Land System and its Relation to Education in the United States. The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society, 1(2), 132-157.

Weeks, B. E. (2023). Emotion, Digital Media, and Misinformation. Emotions in the Digital World: Exploring Affective Experience and Expression in Online Interactions, 422.

Weston, A. (1984). The two basic fallacies. Metaphilosophy, 15(2), 148-155.

Wilson, M. J. W. (2015). The rhetoric of fear and partisan entrenchment. Law & Psychol. Rev., 39, 117.

Winter, J., & Jackson, C. (2004). The conversation gap. Jonathan Winter.

Legal, Permissions, and Contact Information

Author:

Dr. David M Robertson | ORCID iD

Wichita, Kansas

Permissions Notice:

This document and its contents, including all associated theories, analyses, and clinical interpretations, are the intellectual property of the author unless otherwise cited. It is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License unless otherwise noted.

-

You may share this document in its original, unaltered form for non-commercial purposes.

-

You may not alter, republish, or sell any portion of this work without express written permission.

-

Excerpts and citations are allowed with proper attribution to the author and source website: https://www.dmrpublications.com

Collaboration & Inquiries:

To discuss research collaboration, consultations, or publication rights, please contact the author directly at grassfireindustries@gmail.com

Last Update: N/A

This theory is being released directly to the public—not due to a lack of merit but because of the unfortunate constraints typically imposed by academic bureaucracy and disciplinary silos.

This content bridges several domains—Leadership, Psychology, and Behavioral Science—areas that often fall outside the scope of most narrowly focused journals. Rather than wait for editorial gatekeepers hesitant to challenge prevailing norms, this work is offered freely to practitioners and researchers willing to explore beyond outdated frameworks.

Moreover, this theory is merely one part of four. Epistemic Rigidity Theory works with the Adversity Nexus Theory, the Contrastive Inquiry Method, and the 3B Behavior Modification Model.

For those interested in extended analysis or collaborative inquiry, I encourage you to reach out.

Copyright © 2024 – Present. Dr. David M. Robertson, MSL, VL2. All rights are reserved, including those for text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

Keywords: Contrastive Inquiry Method, Socratic Questioning, Critical Thinking, Epistemic Rigidity, Contrasting Perspectives, Structured Inquiry, Cognitive Flexibility, Problem-Solving, Balanced Understanding, Situational Analysis.