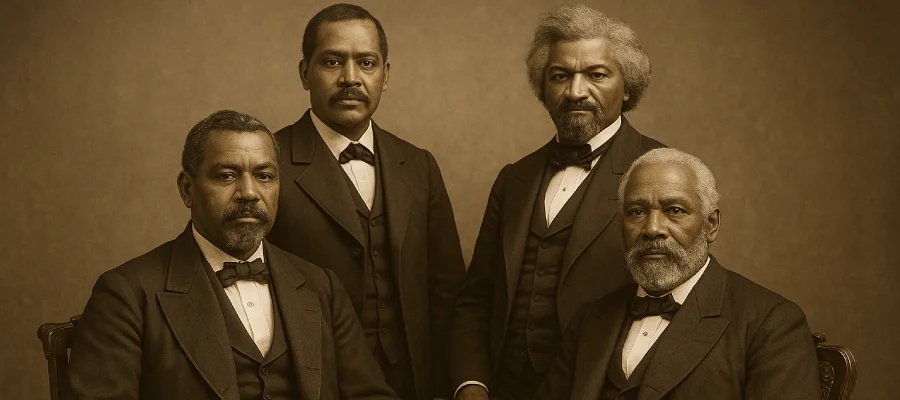

Forgotten Black Leaders of Reconstruction

There is a chapter in American history that has been deliberately omitted from public education. What they told you was that the end of the Civil War in 1865 marked a turning point in American political life. That’s true. However, what they forgot to mention was that for the first time in the nation’s history, formerly enslaved men gained not only the right to vote but also the right to hold public office. It’s true. The post–Civil War era witnessed the emergence of numerous black leaders in public office.

Unfortunately, the same powers that opposed their rise were conspiring to do something about it. Reconstruction was a period of unprecedented political participation for African Americans, yet by the early twentieth century, this progress had been nearly erased by the Democrats. The systematic rollback of Black representation was not accidental but the result of deliberate political, legal, and violent campaigns, largely driven by the Democratic Party in the South.

Federal Representation: Senators and Representatives

Between 1865 and 1912, a total of 2 African American U.S. Senators and 20 African American Representatives served in Congress. Every one of these men was a member of the Republican Party. Their party affiliation reflected the political realities of the time: the Republican Party was founded on anti-slavery principles and became the political vehicle for emancipation, the Civil War victory, and Reconstruction legislation. The Democratic Party of this era, particularly in the South, was the party of white supremacy, actively opposed to Black suffrage and representation.

- Senators:

- Hiram Revels (R–Mississippi, 1870–1871)

- Blanche K. Bruce (R–Mississippi, 1875–1881)

- Representatives included figures such as:

- Joseph Rainey (R–South Carolina, 1870–1879), the first Black member of the House.

- Robert Smalls (R–South Carolina, 1875–1879; 1882–1883; 1884–1887).

- George Henry White (R–North Carolina, 1897–1901), the last African American Representative until 1928.

By 1901, the number of African Americans in Congress had dropped to zero. However, this was not because of a lack of candidates or interest. Instead, it was because of targeted disenfranchisement measures that removed Black voters from the electorate.

State Legislatures: A Short-Lived Majority

The most striking gains for African Americans during Reconstruction occurred at the state level. Many are completely unaware that more than 600 Black men served in Southern state legislatures between 1865 and 1877. In South Carolina, Black legislators even held a majority in the statehouse during parts of the 1870s. In fact, African Americans also served in state legislatures in Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and other Southern states. Why weren’t you told?

In reality, these victories were made possible by the federal enforcement of Reconstruction laws and the presence of Union troops, which curtailed the power of violent, Democrat-led organizations like the Ku Klux Klan. Black political participation was widespread, and for a brief period, Southern politics reflected a more democratic vision than the nation had ever seen.

(Dropdown): State-by-State Black Representation, 1865–1912

Alabama

- About 100 Black legislators served in the Alabama state legislature during Reconstruction.

- Representation peaked in the 1870s, with several individuals holding county offices.

- Disenfranchisement laws in the 1890s ended this presence almost entirely.

Arkansas

- About 85 Black legislators served in the state assembly between 1868 and 1893.

- Arkansas had a mixed record but remained more restrictive than South Carolina or Louisiana.

Florida

- Between 1868 and 1902, more than 60 Black legislators served in Florida.

- Florida’s 1868 constitution opened the door to representation, but it was steadily dismantled after 1885.

Georgia

- Initially, 32 Black legislators were elected in 1868, though they were expelled by white Democrats and only reinstated under federal pressure.

- Over 100 served in total during Reconstruction, but by the mid-1870s, representation collapsed.

Louisiana

- Over 125 Black legislators served in the state legislature.

- Louisiana was notable for its strong Black political class in New Orleans.

- By the 1890s, segregationist constitutions removed them from office.

Mississippi

- More than 220 Black legislators served between 1868 and 1890.

- Mississippi had the highest proportion of Black officeholders, including both U.S. Senators (Revels and Bruce).

- After the 1890 Mississippi Constitution, numbers plummeted to near zero.

North Carolina

- About 30 Black legislators served between 1868 and 1901.

- North Carolina sent George Henry White to Congress, the last Black Congressman before the long drought (1901–1928).

South Carolina

- Over 300 Black legislators served, making South Carolina unique.

- In the early 1870s, the state had a Black majority in its lower house.

- By the 1895 constitution, representation was destroyed.

Tennessee

- Numbers were far lower, but about 14 Black legislators served in the statehouse between 1872 and 1888.

- Tennessee followed the same trajectory of disenfranchisement as its Deep South neighbors.

Texas

- About 30 Black legislators served between 1868 and 1900.

- Texas adopted strict disfranchisement by the 1890s, reducing the number to zero.

Virginia

- About 90 Black legislators served between 1869 and 1890.

- Virginia saw steady participation until the Jim Crow laws in the 1890s.

Totals and Patterns

By 1912, nearly all Black officeholders had been eliminated through Jim Crow laws and state constitutional changes. Nonetheless, over 600 Black legislators served across the South between 1865 and 1877, and South Carolina and Mississippi accounted for the highest concentrations.

The Return to Zero

By the 1880s and 1890s, the progress made during Reconstruction was dismantled through Jim Crow laws, which codified racial segregation and disenfranchised Black citizens. Poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses were deliberately constructed to prevent Black men from voting. Violence and intimidation at the hands of groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and the White League further suppressed participation. State constitutions were rewritten across the South to cement disenfranchisement.

The Democratic Party was the chief political actor in this process. After regaining control of Southern legislatures in the late 1870s, Democrats implemented measures to ensure that African Americans were locked out of the political system. The Republican Party, which had once defended Black political rights, became less effective in the South as its national priorities shifted. By 1912, African American representation in Congress and in most state legislatures was reduced to nearly zero.

(Dropdown): The Myth of the “Party Flip”

The claim that Democrats and Republicans “switched sides” on race is, putting it nicely, a political myth. However, it’s a myth that the Democrats needed to erase continuity and hide accountability. From 1865 through Jim Crow, the Democratic Party consistently opposed Black political power. Before the Civil War, Democrats defended slavery. After the war, Democrats built segregation, wrote Jim Crow laws, and violently suppressed Black voters. That through-line never changed.

The Republican Party, by contrast, was founded as the anti-slavery party and remained the party of Reconstruction and civil rights legislation well into the 20th century. In reality, the Civil Rights Acts of the 1960s were passed with stronger Republican support in Congress than Democratic. What changed was geography: over time, white Southern conservatives shifted to the Republican Party, while Black voters, for economic and social reasons, began to move toward the Democratic coalition.

To call that migration a “flip” is dishonest. Democrats before and after were still Democrats, voting to preserve their interests. The packaging changed, but the party’s legacy of obstruction, segregation, and racial politics did not. The “flip” narrative is propaganda that covers nearly a century of Democratic suppression of Black political power and is easily debunked if you do any sort of objective research.

Why This History Matters

The erasure of Black political representation following the Civil War is a pivotal aspect of American history. Its omission contorts reality and fosters division. The truth remains: between 1865 and 1877, African Americans demonstrated their capacity for leadership and governance, serving in both federal and state offices. Yet by the early twentieth century, systemic disenfranchisement and racial violence nearly eliminated this progress. These facts demonstrate both the political nature of the rollback and the extraordinary effort invested in distorting the truth.

Think back to your own history classes. Was any of this taught? For most Americans, it was not. That omission was not accidental. As the Democratic Party shifted in the twentieth century to securing Black political participation through economic and social incentives, it became necessary to obscure its long record of building and defending segregation. The “party flip” narrative provided a convenient distortion, allowing Democrats to present themselves as the historic champions of civil rights while deflecting from their central role in suppressing Black political power after Reconstruction.

You might be tempted to say, “But that’s unethical. They wouldn’t do that.” In reality, liberal-dominated state education systems reinforced the distortion by downplaying or omitting Reconstruction’s Black political achievements. Generations were left with a skewed understanding of how and why Black representation was destroyed. If you think that is an exaggeration, consider this: Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate Army, once called slavery an “abomination.” He and his wife even educated enslaved people to prepare them for freedom. You probably were not taught that either, but a bigger question remains: if the Civil War was only about slavery, then what was Lee truly fighting for? Now, what else haven’t you been told? Or worse, what were you told that was blatantly wrong?

I want you to understand that he who controls education controls history, and he who controls history controls power. He who controls education decides what a generation remembers, and what it forgets. He who controls education controls the narrative, and the narrative controls the nation. If more people understood the truth about Reconstruction and the deliberate destruction of Black political power, who would stand to lose?

A significant part of leadership is making informed decisions. That is rather difficult when the information you base your decisions on is wrong. We should all be angry. However, we should also wonder why there has been no push to correct the record. Perhaps this gives us some insight into why conservatives have been pushed to avoid or even hate education. It’s probably not a coincidence. Perhaps, it’s just another example of perception warfare.

Author’s Note: If you pull nothing else from this article, let it be that this is not just about history. It is about who controls what you know, and therefore, how you think, act, and vote. If you would like to go down that rabbit hole, check out my article titled, The Delusion of Choice is Federalism.

Keep Learning: